Star Trek is Better Than Star Wars

Being a nerd means that you will inevitably get involved in a lot of esoteric debates which rage on for literally decades. Debates such as Magic the Gathering vs. Warhammer, Starcraft vs. Command and Conquer, Marvel vs. DC, Vampire the Masquerade vs. Werewolf the Apocalypse. These are the battles which define our existence as hopeless dorks.

The most important debate in nerd culture however, the question that gets to the heart of everything that nerd-dom is based on is this: which is better, Star Trek or Star Wars?

Well, to be direct I will begin by saying that Star Trek is vastly superior to Star Wars.

This however is NOT to say that I don’t love Star Wars. I have always loved Star Wars. I don’t want anything that I say to be misconstrued. I’ve seen all six movies more times than I can count, I used to photoshop lightsabers into pictures of myself when I was in high school. I love Star Wars. I just think that Star Trek is better.

The entirety of the Star Wars canon is contained within six films. Star Trek however spans six television series encompassing 726 episodes in all and eleven feature length films. The scope of Star Trek means that by its nature it is an endeavor to really get to the know the universe in any great depth. This would explain why Star Wars is generally more popular; you can watch every Star Wars film in a day. Star Trek however takes time and dedication to appreciate. If you watched one episode or one movie per day, it would still take you over two years to cover all of Star Trek.

People appreciate things that are easily encapsulated. Star Wars follows a single story arc which is conducive to tourists, part-timers, and dabblers. True Star Trek fans cannot dabble.

Star Trek is more than a single story, more than a single set of characters or even one overall objective. The Star Trek universe is a huge canvas that allowed many different creative minds to collectively ponder some of life’s more important questions. The vastness of the Star Trek canon serves the purpose of investigating, contemplating, and explaining every minute aspect of what it means to be a human being.

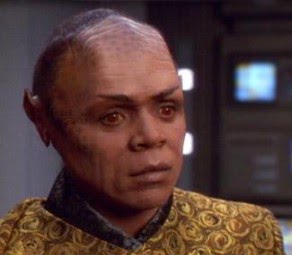

The human condition – moreso than any interstellar politicking, supernova’s explosion, time travel, or laser beams – was the true subject of Star Trek. This is why in every series there was at least one character struggling with defining their humanity. In TOS it was Spock the half-Vulcan science officer. In The Next Generation it was Data, the android who struggles to continually be more human. In Deep Space 9 it is Odo, the shapeshifter who tries to fit in among humanoids by maintaining a humanoid form even though his species is more comfortable as a puddle of liquid. In Voyager both the holographic Doctor and the former Borg drone Seven of Nine struggle to find their place in human culture.

Another reason that people gravitate toward Star Wars is because there is almost no moral ambiguity. Star Wars presents a moral dichotomy that conforms to lowest common denominator of human ethical sensibility. The “light” side of the force – peace-seeking, contemplative, and always fighting with friendlier colors of lightsaber – is battling the “dark” side of the force – confrontational, deceptive, and always fighting with red lightsabers. Light vs Dark, the lack of subtlety is comforting but makes for a less pervasive and verisimilar storyline.

Star Trek on the other hand is neck-deep in shades of grey. It’s hard to watch an episode of any of the Star Trek series without feeling a deep ethical conflict. It’s never 100% clear of what the right thing to do is. Unlike in Star Wars where the multitude of aliens exist solely to provide a colorful supporting cast for an all human group that actually drives the story, the aliens in Star Trek have unique and important cultural, biological, and mental characteristics that actually determine the arc of each story.

Moral allegory is a huge part of Star Trek. By creating scenarios where there is no clear right or wrong, no clear light or dark side, we are forced to contemplate our choices. By using specific components of different species, we are able to create moral dilemmas with real emotional weight, scenarios that could never exist in real life. By the introduction of species that could realistically be defined as pure evil, or species that are telepathic, species that live for hundreds of years through symbiotic reincarnation, or species that are nearly omnipotent, species that are cybernetic, inorganic, or non corporeal we can push the bounds of what defines personhood, what are the rights of sentient beings, how can moral standards be applied evenly to species that are so inherently dissimilar?

Inevitably in any discussion about the merits of Trek vs Wars, there is the assertion that the action in Star Wars is better than the action in Star Trek. That is a point I don’t hesitate to concede. No handheld phaser shootout or starship battle in Star Trek begins to compare to the amazingly choreographed lightsaber duels in Star Wars. I will however assert unequivocally that this is a very weak element to hinge an argument on. At the end of the day, what makes for exciting entertainment doesn’t necessarily make for enlightening literature.

Star Trek is also superior because it is grounded in this place and timeline. By setting Star Wars in “a galaxy far away” Lucas lets himself of the hook for continuity issues. Star Trek however has to work with a future that – however improbably – evolved naturally out of the present we live in. Star Trek begins with us, right now, on Earth, and expands and unfolds and progresses. By limiting itself in one area, the Star Trek universe has a basis from which to grow indefinitely while remaining emotionally compelling.

Star Trek emphasizes the political and the rational, and an overwhelming number of episodes focus on logical progression of scientific ideas and applying just political principles to governing internally and exploring externally. Star Trek never dealt with what could be called spirituality in a traditional sense (temporally aberrant wormhole-residing aliens in DS9 notwithstanding) and there are no overarching superstitious themes. Star Wars however deals almost exclusively with the spiritual. While there is a political subplot, it is a one dimensional backdrop to Luke/Anakin’s religious maturation/unraveling/redemption. The defeat of the evil Galactic Empire ultimately doesn’t hinge on savvy political maneuvering, guerrilla warfare, or espionage, it hinges on Luke’s self-realization as a religious messiah.

The plot of Star Wars is intrinsically elitist. While any story has to emphasis certain characters over others in order to drive the plot, the Star Wars storyline explicitly states that certain characters are born more important than others. It is typical of a religious viewpoint that some messiah characters will be more important than others no matter what happens. This is shown most obviously when Anakin/Darth Vader is redeemed at the end of The Return of the Jedi.

Vader we know has killed countless numbers of people. He has ordered them killed as a military commander and in the prequels he personally slaughters everyone in the Jedi temple, including children. His only redeeming action is to kill the Emperor when he tries to kill Luke. While that act was dramatic, it hardly constitutes a real change in Vader’s moral compass. Even the most ruthless murderers would likely take revenge on a person trying to murder their son. But we are presented with Anakin completely redeemed as a spectre, standing with Obi Wan. This is an obvious way of saying that the rules do not apply to Anakin or Luke, and that their lives are simply more important than everyone else’s.

Star Trek plots are always overwhelmingly egalitarian. One of the consistent themes is the need to treat our enemies, ostensibly “lower” forms of life, and even artificial species with respect and dignity. It’s rare that even an unnamed character in Star Trek dies without significant attention paid to it. This is somewhat less true in TOS, spawning jokes about “the unnamed officer who goes along on away missions simply to be killed dramatically”. Even accounting for some merciless killing in TOS, Star Trek maintains and enormous amount of respect for all characters. We are told time and time again in Star Trek of characters who progress because of hard work and dedication instead of simply being born “special”.

Boundaries give a sense of realism to storylines. While both Trek and Wars are guilty of extensive departures from realistic boundaries, reality keeps Star Trek on a much shorter leash than it does Star Wars. Although almost all extraordinary phenomena that occur in one occur in the other as well (except for Q), Star Trek remains grounded in science by at least offering explanations for how things happen – even if those explanations aren’t at all scientifically feasible in the sense that we understand science. Star Wars simply waves a hand and chalks all supernatural occurrences up to The Force.

Star Trek, even with all of its occasional clumsiness and continuity issues still clearly surpasses Star Wars by every meaningful narrative standard. All of the problems with Star Trek all come from its single biggest strength, namely its huge expansive universe that has allowed for many creative minds to control the arc of many interlinking stories. Being ambitious with a project means that there are more opportunities for minor solecisms, and being relatively conservative with a single story arc means that there are fewer such opportunities. The tradeoff is obvious.

In order to illustrate a few of the points I’ve asserted I would like to provide a few narrative examples of powerful moments in Star Trek. This list is by no means exhaustive or even chronological, it is simply a brief listing of some of my favorite moments in Star Trek.

1. “The Measure of a Man”. In this TNG episode, Data the android is put on trial to determine if he is a sentient being or if he is the property of Starfleet. This scenario draws obvious parallels to the Dred Scott Supreme Court case in which the fugitive slave was found to be only 3/5 of a human being.Captain Picard believes Data to be a sentient being but also recognizes that the court’s decision could hold dire consequences for future androids like Data if he is ever successfully reproduced. Classifying Data as an object would mean that all future Data-like androids would be born into a life of bondage. A troubled Picard considers a future where humanity can create androids as slaves. He takes the longview and successfully argues against classifying Data as property.

2. “Lonely Among Us”. In this episode early in TNG, Commander Riker makes the claim that his people “no longer enslave animals for food purposes”. Almost all food on a starship is created by machines called replicators that materialize food from thin air. In this way the meat that the crew eats doesn’t come from animals, it simply comes into existence. Later episodes do contradict this, there are instances where people eat eggs. Some characters hunt occasionally. And in DS9 Captain Sisko’s father owns a seafood restaurant that serves real fish.However, most humans in the Star Trek storyline no longer rely on animals for food. This is an example of how progressive the Star Trek universe is, even episodes written in the ’80s. It assures us that in the future there will be an end to religion, racism, poverty, sexism, and large-scale animal exploitation.

3. “I, Borg”. In this TNG episode, the crew of the Enterprise rescue a single Borg drone. For those unfamiliar, The Borg are a cybernetic species that travels through the galaxy kidnapping other species and ‘assimilating’ them into their collective by attaching robotic parts onto their bodies and hooking their brains up to a collective consciousness. The Borg represent the closest thing to irredeemable evil that we encounter in all of Star Trek.After rescuing the single Borg drone and nursing him back to health, the crew comes up with a plan to implant a computer virus in his brain and send him back to the collective. The plan would effectively destroy the entire Borg collective. Captain Picard overcomes his personal vendetta against the Borg (he had been previously assimilated into their collective and was emotionally scarred by the experience) and vetoes the plan, which he calls genocide.

4. “The Drumhead”. In this TNG episode an admiral comes on board the Enterprise to investigate what was thought to be a sabotage by a double agent on the ship. In the end it is determined that there was never a sabotage or a conspiracy or a double agent. But the admiral is so paranoid that she goes on a rampage, interrogating and accusing anyone on the ship who opposes her of being a traitor to the Federation. The situation quickly becomes a witch hunt led by the admiral. Picard attempts to get her to listen to reason and she summons him for questioning.She calls his integrity into question and he responds by quoting the admiral’s father, a famous judge who defended civil liberties and due process. The short speech he gives is powerful if brief: “‘With the first link, the chain is forged. The first speech censured, the first thought forbidden, the first freedom denied, chains us all irrevocably.’ Those words were uttered by Judge Aaron Satie, as wisdom and warning. The first time any man’s freedom is trodden on, we’re all damaged.” Later in the same episode Picard warns that “the road from legitimate suspicion to rampant paranoia is very much shorter than we think.”

5. “Rejoined”. In this episode of DS9 we are introduced to a particular feature of Trill culture. The Trill are two species that are joined symbiotically. There is a small vermiform creature that inhabits the stomach of a humanoid. The smaller species lives for much longer than the humanoid species (at least nine times as long) so when the humanoid host dies, the symbiont is passed onto another host. The personality of each Trill is a balance of characteristics from the symbiont and the host. Each Trill carries the memories of all its past hosts. In a lifetime, Trills can go through many hosts, some of whom will be male, some female.In “Rejoined”, the plot is driven by the fact that in Trill culture, it is forbidden for a Trill to become romantically involved with the partner of a previous host. One of the main characters in DS9, Dax is a Trill, and in one of her previous hosts she was a humanoid male and was married to another Trill that was a humanoid female. Both of the symbionts have been transferred to other hosts and Dax has to work with the new host of her old host’s wife. They become romantically involved and conflicts arise about whether or not they can follow through with their love given that it would mean they would be ostracized from Trill society. The episode subtly addresses a number of sexual minority issues, and looks at love in a way that is very post-gender.

6. “Tuvix”. In this episode of VOY, a transporter accident merged two crew members, Tuvok and Neelix at the cellular level, creating one person, Tuvix. Tuvix had the memories and abilities of both Tuvok and Neelix and was a physical hybrid of the two but had a distinct personality. It was weeks before a procedure was developed which could separate Tuvix back into two people. Tuvix however considers himself a sentient being and asserts that separating him back into two people is no different than killing him. Captain Janeway’s decision to force Tuvix to undergo the procedure was – for me personally – one of the most emotional and ethically ambiguous moments in all of Star Trek. I nearly cried when Tuvix is asking the crew for help, to stop Janeway from forcing him to undergo the procedure.

Through the lens of a technologically advanced future, Star Trek gives us a glimpse of what humanity could be: a people united to explore the galaxy and seek out peaceful contact with new forms of life. We can see a triumph of egalitarianism and respect for the dignity of sentient beings, a dedication to civil rights, deference to alien culture’s sovereignty, and a commitment to resolving conflicts peacefully. Star Trek expands the horizons of our compassion, urges us to consider complex moral questions, and continually prompts us to be a better people.